On this, the 70th Anniversary of Operation Overlord, the D-Day Landings in Normandy, June 1944, here’s part of the chapter from my book WHEN EAGLES DARED discussing the events of that June night and the following day, and how it has been depicted on film.

EXTRACT FROM ‘WHEN EAGLES DARED: THE FILMGOERS’ HISTORY OF WORLD WAR II’

PUBLISHED BY I.B. TAURIS

ALL TEXT © Howard Hughes 2011/2014

In the spring of 1944 the Allies kept the Germans guessing as to where further landings in mainland Europe would occur. The Russians were eager for the Allies to open up a second front to divide Hitler’s forces and resources. The film I Was Monty’s Double (1958 – Heaven, Hell and Hoboken) told one of the most extraordinary war stories. To convince the Germans that the invasion would come from North Africa, General Montgomery made a tour of Gibraltar and North Africa in preparation for the attack. But the real Montgomery was planning Operation Overlord in England. The ‘Monty’ doing the rounds in Africa was in fact actor M. E. Clifton James, a lieutenant in the Pay Corps, whose remarkable resemblance to Montgomery earned him a unique place in history. James was appearing in theatre revue Khaki Kapers when he was convinced by British Intelligence to impersonate Montgomery. John Mills and Cecil Parker play the intelligence officers who engineer the ruse. German agents swallow the bait and begin to spread misinformation regarding Montgomery’s whereabouts, which leads to assassination attempts and a kidnapping involving a U-boat. The film was based on James’ 1954 book of the same name. For actor James it was the role of his life, in more ways than one. In the film James played himself and also portrayed Montgomery, in cleverly edited scenes which are spliced with stock footage of the real Monty. The film ends with James watching newsreels of the D-Day landings, having succeeded in diverting 60,000 German troops and a Panzer division into protecting a non-existent invasion attempt from North Africa.

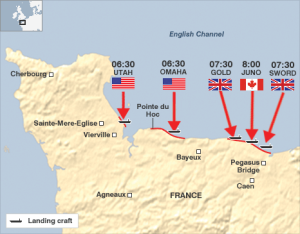

Hitler also retained 12 Divisions in Norway as a result of the Allies creating a fictitious British Army who were stationed in Scotland and were preparing to invade. The Germans also suspected the invasion would land in the south of France, Yugoslavia or even Greece, but the real target was always to be France’s Atlantic coast. Preparations were afoot in England for Operation Overlord, the most important, complicated and decisive strategy of the war. The obvious invasion route from England was to the Pas-De-Calais. The shortest route was between Dover in Kent to Calais in Nord-Pas-De-Calais, France (the route the Channel Tunnel now uses). The Germans were kept guessing by subterfuge (as fake plans fell into the Germans’ hands), while the French Resistance worked tirelessly to keep the occupying forces on their toes and Allied bombers destroyed vital bridges. Hitler’s Atlantic Wall sea defences were at their strongest in the Pas-De-Calais area, with concrete and steel bunkers housing formidable guns, machine gun nests, webs of lethal barbed wire and minefields. There were also anti-tank and anti-landing craft defences: tetrahedral spikes that would disembowel landing craft and concrete ‘Dragon’s Teeth’, making routes from the beach impassable. But large portions of this Atlantic Wall were poorly defended and some emplacements were dummies to confuse the Allies. The area of Normandy was equidistant from England’s south coast ports – from Falmouth in the west to Newhaven in the east, which would be important in supplying Allied forces in the subsequent battle for France. Thus the coastline between Cherbourg (on the Cotentin Peninsula) and Le Havre became the most famous beaches in history.

Dwight D. Eisenhower of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) oversaw the operation, with Montgomery in command of the ground troops. Operation Overlord was eventually set for midnight of the 5-6 June 1944, where a break in June storms would enable the 5000-strong armada (including 600 warships) to travel safely across the Channel. The plan fell into two phases. The airborne assault was to secure important objectives inland. The amphibious assault would land ground troops and their equipment (including armour) on the coast. Infantry were ferried across the Channel on transporter ships and then loaded into landing craft as they neared the beaches. 176,000 troops travelled with the armada to land on five beaches – codenamed Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah – in the Bay of Seine, roughly between the mouths of the Rivers Orne and Vire. On the left flank, British and French forces of the British 1st Corps landed at Sword, near Ouistreham. Canadian forces of the 1st Corps landed at Juno beach and the British 30th Corps landed at Gold. To the west, the US 5th Corps landed at Omaha and on the far right flank, the US 7th Corps landed at Utah, although due to navigational difficulties they landed in the wrong place. The invasion’s exposed flanks were protected by airborne assaults. The British 6th Airborne Division secured vital bridges and disrupted communications on the left flank, while the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions landed on the right. Arriving at night, in gliders and by parachute, they completely surprised the defenders, though the 82nd Airborne suffered heavy losses when some of them overshot the drop zone and landed on the fortified garrison town of Sainte-Mère-Église. Following a bombardment of the beaches – which commenced at 5.30am – the invasion began landing troops onto the beaches at 6.30, with most assaults being highly successful. The naval barrages and concentrated air support weakened the German defences before the Allies landed. Only Omaha faltered, with sustained German fire pinning the US troops to the beach, though this was eventually overcome. By midnight of the ‘longest day’ five bridgeheads had been established.

When it comes to Operation Overlord in the cinema, there’s only one contender: The Longest Day (1962). As a fitting tribute to the greatest operation of the war, Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck’s labour of love resulted in the finest World War II combat film. Cornelius Ryan’s 1959 book The Longest Day was dedicated ‘For all the men of D-Day’ and told the epic story with alacrity and drama, which made it a page-turning bestseller. Ryan worked on the screenplay, with additional material by Romain Gary, James Jones, David Pursall and Jack Seddon. The book and film told the story from several protagonists’ perspectives: French, German, British and American. To facilitate this narrative feat, with many speaking parts depicting real people, Zanuck assembled a stellar array of actors. He began casting in June 1961. This resulted in a once-in-a-lifetime ‘spot the film star’ cast, with some of the era’s biggest names. The film is not only interesting as a historical document of the events of D-Day, but also a snapshot of the film stars of the day. There is no title sequence – simply the title The Longest Day – and the cast are listed alphabetically at the end, to prevent egotistic billing arguments.

The film begins in Occupied France at the moment of its deliverance. Radio messages convey coded instructions to the French Resistance. When a line from a Verlaine poem is broadcast (‘The long sobs of the violins of autumn’), the Resistance know that when the next line is transmitted (‘Wounds my heart with a monotonous languor’) the invasion will begin within 24 hours. They disrupt the German lines of communication, destroying telephone cables and railway lines. In advance of the landings in Normandy, diversions convince the Germans that Cherbourg is under attack. ‘Rupert’ (a mechanical parachutist who explodes on impact with the earth) and many like him are dropped to confuse the enemy. In the dead of night, the Allies airborne assault begins – the pathfinders set up DZs and LZs (Drop Zones for paras and Landing Zones for gliders). British glider troops led by Major John Howard (Richard Todd) swoop on Pegasus Bridge on the Orne River, with instructions to ‘Hold until relieved’. Their gliders land close to the bridge and the objective is swiftly secured. This surprise attack, deftly edited and staged for maximum impact, is a contender for the finest action scene in war cinema. When elements of the 82nd Airborne miss their DZs, most end up in a flooded swamp area, but many plunge into Sainte-Mère-Église, a Nazi garrison HQ. They drift helplessly into the town square, lit up by a building which has been ignited by a flare. Paratrooper John Steel (played by Red Buttons) is suspended from the church bell tower by his chute and watches the grim bloodbath unfold as few of his comrades hit the ground alive. Later their commander Colonel Ben Vandervoort (John Wayne) and the relief column discover the massacre, with paratroopers’ corpses still limply hanging from telegraph poles and trees. Vandervoort’s grittily snapped ‘Get ‘em down’ is one of the Duke’s finest screen moments.

The production boasted a long list of Military Consultants, many of whom are depicted in the film. Zanuck spent three months researching his subject. To ensure authenticity, he filmed his D-Day landings on the actual beaches and locations, with interiors lensed by Zanuck himself at Studios De Boulogne. 31 separate exterior locations in Normandy were used. In the 1968 documentary D-Day Revisited, photographed by Henri Decae and Walter Wottitz, and directed by Bernard Farrel, Zanuck returned to Normandy for the assault’s 25th anniversary and discussed the locations he’d used in the film, including the concrete bunker gun emplacement atop a 100-foot cliff at Pointe Du Hoc, which still stands as a monument. Other locations used in the film include the town of Saint-Mère-Église in Manche, the Orne crossing at Pegasus Bridge and the harbour fishing village of Ouistreham, Calvados, in Lower Normandy. The film was helmed by four directors (and uncredited Zanuck) but unlike Tora! Tora! Tora! you can’t see the joins. Shooting simultaneously to save time, Ken Annakin filmed the British exterior episodes, Andrew Marton and Gerd Oswald shot the US episodes and Bernhard Wicki shot the German sequences. Co-producer Elmo Williams co-ordinated the battle episodes and the use of archive footage was kept to a minimum. Principal photography began in August 1961 and by autumn they were shooting the beach landings. By then the assigned budget of $8 million from Twentieth Century-Fox had been eaten up and Zanuck was financing the project himself.

The film’s monochrome cinematography reinforces the film’s realism, while the widescreen 2.35:1 CinemaScope ratio adds to its epic scope. Jean Bourgoin and Walter Wattitz won Oscars for their cinematography. Best Special Effects Oscars also went to Robert MacDonald (visual) and Jacques Maumont (audible). Maurice Jarre composed the memorable score, which deploys rolling, relentless marching drums to create tension. The opening scene – a fade from inky blackness to a shot of a wave-lapped beach, with an upturned GI’s helmet lying in the sand (an image used for the film’s poster) – is accompanied by ominous timpani. The distinctive ‘dun-dun-dun-daarr!’ opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony are heard – this is the ‘V’ for victory sign in Morse Code (dot, dot, dot, dash). Only at the film’s conclusion, with victory won, do we hear Jarre’s famous theme song. Composed by singer Paul Anka and arranged by Mitch Miller, this lively march tells of the longest day’s heroism (‘Many men will count the hours, as they live the longest day’). In the film it is sung rousingly by a chorus, though Anka also recorded a version of the song as a tie-in with the film.

The Longest Day boasts the most impressive cast list of all time. Advertising trumpeted ‘42 Stars’ on display. Even with the film’s 168-minute running time, few had time to shine for long and some appearances are literally to deliver one or two lines, or as a face in the crowd. John Wayne was top of the pile as Colonel Ben Vandervoort, who breaks his ankle on landing and is towed through the action on a wheeled ammo limber. Wayne received $250,000 for the role, while his co-stars received $25,000 each. Robert Mitchum was similarly prominent as Brigadier General Norman Cota of the US 29th Division on Omaha beach and Henry Fonda played arthritic General Theodore Roosevelt, the president’s son, who was the oldest member of the assault team. Zanuck took out what he termed ‘a little insurance’ in the canny casting of several young actors – many of whom were also singers – as US Rangers, infantrymen and paratroopers, to hook the teenage audience. The youngsters briefly on display during The Longest Day include Fabian, Paul Anka, Tommy Sands and Sal Mineo, but their names appeared prominently on posters and ensured the film drew a wide audience. There were many established American names in supporting roles. Robert Ryan played Brigadier General James Gavin, Rod Steiger was a destroyer commander off Normandy, Eddie Albert was Colonel Thompson on Omaha beach, Stuart Whitman played paratrooper Lieutenant Sheen, Edmund O’Brien was General Raymond ‘Tubby’ Barton, Mel Ferrer played Major General Robert Haines and Steve Forest was the 82nd Airborne’s Captain Harding. Other US soldiers were played by Mark Damon, Ray Danton and Roddy McDowell, while Richard Beymer (Tony in West Side Story) had a key role as paratrooper ‘Dutch’ Schultz, who manages not to fire his gun throughout the entire day and ponders at the film’s close: ‘I wonder who won?’

Richard Todd, Kenneth More, John Gregson and Richard Burton were familiar to audiences from 1950s British war films. Bearded More played Captain Colin Maude, the Royal Navy Beach Master, who orchestrates the landing on Sword with his bulldog Winston. John Gregson played the 6th Airborne’s padre, who is seen diving in a river for his lost Communion set. Burton played RAF pilot Flight Officer David Campbell, who is found slumped, badly wounded, in a farmyard – his leg is held together with safety pins. No one can deliver lines like ‘Ack-ack over Calais’ or ‘Split right open from the crotch to the knee’, like Burton, with his distinctive clipped Welsh tone. Peter Lawford played commando Lord Lovat of the Green Beret British Special Service Brigade, whose troops go ashore on Sword to the accompaniment of Scots piper Bill Millin. Richard Wattis played a paratrooper, Leo Genn was Brigadier General Edwin P. Parker, Michael Medwin played a Bren Gun driver stalled on the beach and Donald Houston played an RAF pilot. Canadian Alexander Knox was Major General Walter Bedell Smith. As bickering comic relief, Norman Rossington played cockney Private Clough and a soon-to-be James Bond Sean Connery played Irishman Private Flanagan on Sword. Leslie Phillips can be seen briefly as Mac, an RAF officer who is being sheltered by the Resistance – his character is a precursor of the British airman in the TV sitcom Allo! Allo!

As the film employed ‘Top talent of four countries’, the French and German contingent was considerable. Among the famed French players was Arletty as Mother Superior to a group of nuns (trained nurses who tend the French wounded); Jean-Louis Barrault was Father Louis Roulland; Jean Servais was naval Amiral Jaujard of the Forces Français Libres; and Bourvil was the excitable Mayor of Colleville. Christian Marquand played Commandant Philippe Kieffer of the Commando Français, with Georges Rivière his aide, Sergeant Guy De Montlaur. Irina Demick played Resistance fighter Janine Boitard and Italian Maurice Poli was her fiancé Gille. The German top brass included Major General Günther Blumentritt (Curd Jürgens), Colonel General Alfred Jodl (Wolfgang Lukschy), Major General Dr Hans Speidel (Wolfgang Büttner), Field General Gerd Von Rundstedt (Paul Hartmann), General Wolfgang Hager (Karl John) and General Erich Marcks (Richard Münch). Wolfgang Preiss played Major General Max Pemsel and Heinz Reincke played Luftwaffe colonel Josef ‘Pips’ Priller, whose depleted squadron consists of two planes. Future ‘Goldfinger’ Gert Fröbe played slobbish Sgt Kaffekanne, who delivers coffee to the coastal gunners on a horse that looks as lethargic as he is. Some world famous historical figures were also depicted: Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay (played by John Robinson), Montgomery (Trevor Reid), Rommel (Werber Hinz) and Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley (Nicholas Stuart), who surveys the invasion from his flagship, Augusta. Henry Grace played Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ike was going to play himself, but makeup artists couldn’t achieve the transformation convincingly.

Once the longest day is underway, the film is a succession of memorable action vignettes. The first sight of the armada through the slit of a German coastal bunker as it materialises from the morning mist is accompanied by Beethoven’s Fifth shuddering on the soundtrack. From his bunker, Major Werner Pluskat (Hans Christain Blech) feels the full force of the Allied naval salvo and yells down the phone to Lt Col Ocker (Peter Van Eyck): ‘Those five thousand ships you say the Allies haven’t got – well, they’ve got them!’ For the action sequences, the French Army loaned the production 3000 men as extras and impressive ordnance gathered from around the world poured onto the beaches, including Sherman tanks, trucks, Bren Gun carriers, jeeps, M3 half-tracks and amphibious DUKWs. These were the so-called Army ‘Ducks’, which were GMC 6×6 trucks with boat-shaped hulls, making them resemble wheeled pontoon barges. For one scene, a real train was blown up to depict the Resistance’s activities. The action scenes are intercut with the German commanders’ attempts to counter the invasion and their incredulity at their own ineptitude: the invasion inconveniently coincides with the absence of many top officers on training exercises. When they request reinforcements, senior German field commanders are informed that the Führer has taken a sleeping pill and can’t be woken. Thus vital Panzer divisions remain in reserve, when their deployment may have turned the tide.

The film’s beach scenes resemble newsreels, as the camera dollies alongside the charging US troops on Omaha beach. A swooping attack by two Luftwaffe planes, which strafe Gold and Juno beaches, is filmed from the perspective of the pilots as they wreak havoc. An impressive helicopter shot (filmed by Ken Annakin on the eighth take, when all other directors had failed) captured the French Commandos from Sword rushing the waterfront of Ouistreham to take a heavily fortified hotel and casino – a brilliantly orchestrated scene which is a swirl of smoke, noise and movement. As they make their way at night through the silent countryside, US paratroopers use click-click ‘crickets’ as signalling devices. Sal Mineo is unfortunate when the two ‘clicks’ which answer his signal are a German soldier levering his bolt-action Mauser rifle. At Pointe Du Hoc, 225 specially trained US Rangers led by Robert Wagner (and including Fabian and George Segal) scale the cliffs under heavy enemy fire with grappling hooks and ladders to take the gun emplacement with 75% losses: in vain as it turns out the guns have never been installed. It is during this scene that a US Ranger mows down German soldiers and then wonders what ‘Bitte, bitte!’ means (it means ‘please’, as in ‘Please don’t shoot us, we’re surrendering’). Jeffrey Hunter had a pivotal role at the film’s climax as engineer Sergeant John H. Fuller, who bravely sets tubular Bangalore torpedoes and explosives to blow a breach in the German defences so the ‘Fighting 29th’ can scramble off Omaha beach. The film ends as troops pour inland to the bridgehead, with Robert Mitchum as Cota enjoying a celebratory cigar and hitching a ride on a jeep (‘OK, run me up the hill son’), as the whistled ‘Longest Day’ march swells.

Always timely, The Longest Day was reissued in 1969, for Operation Overlord’s 25th anniversary

The Longest Day premiered in Paris (as Le Jour De Plus Long) on 25 September 1962, to great success. Edith Piaf sang from the Eiffel Tower for the premiere. The New York premiere followed a month later and the film was a hit with both critics and public. In Italy, The Longest Day won a David Di Donatello Award in 1963 for Best Foreign Film. The Longest Day trailer contains alternative takes of some scenes (for example, the dialogue between Beymer and Burton in the farmyard) and scenes cut from the final version (Mel Ferrer making an announcement to a press conference). In the most widely-seen English version, the actors of various nationalities speak their own languages, with English subtitles. There is also a version with everyone dubbed into English and another version is colourised. The Longest Day grossed $18 million in the US and in its first year took $25 million – according to Zanuck it was seen by more people than any other black and white film. It stands as a testament to the producer’s vision and determination in bringing this pivotal moment in history to the big screen.

WHEN EAGLES DARED: THE FILMGOERS’ HISTORY OF WORLD WAR II (I.B. Tauris)

is available now from booksellers and online in hardback and as an e-book.

I played it this weekend in commemoration of the 70th anniversary and for my late father who was a WW2 vet. Still a terrific motion picture. I had read the book before I ever saw the movie. I always liked Cornelius Ryan’s approach of recording history as a series of true vignettes rather than a fictionalized story with a historical background. I also read his “A Bridge Too Far” and “The Last Battle,” both written the same way. “Is Paris Burning?” also follows his technique. Watching it again, I was impressed with the immensity of the undertaking in filming the event from so many perspectives. Another refreshing angle on “The Longest Day” is that it doesn’t glorify war and Zanuck kept true to that vision, being anti-war himself. A salute to the brave men and women of D-Day and to Darryl F. Zanuck and his team for creating a masterpiece that will forever help us to remember their brave sacrifices.