Trading Places: A 1983 Christmas Comedy That's Still Surprisingly Relevant

The 32-year-old-film, which is centered on insider trading and the culture of poverty, fits into the economic conversations America is having today.

Trading Places isn’t exactly a traditional Christmas film. There are no carolers or large family gatherings. But the trappings of a great holiday movie are there: It does, in fact, take place around the holidays, include a company Christmas party that features a drunk and disgruntled Santa Claus, and focus on themes of generosity (or lack thereof) and redemption.

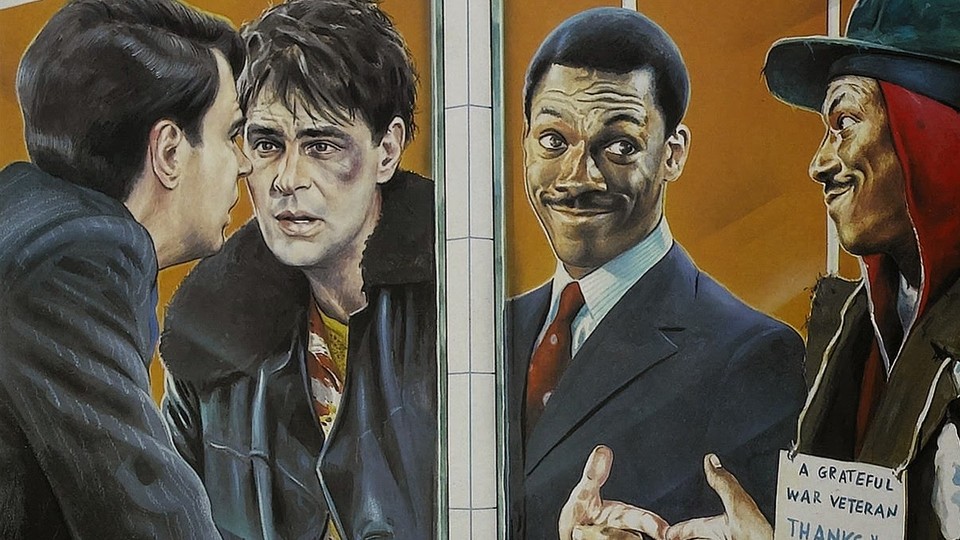

The 1983 comedy stars Dan Aykroyd as Louis Winthorpe III, a wealthy managing director at a Philadelphia commodities-trading firm, and Eddie Murphy as Billy Ray Valentine, a beggar. The plot centers around a grotesque bet made by Mortimer and Randolph Duke, brothers and the owners of Winthorpe’s firm, Duke and Duke. After a run-in between Winthorpe and Valentine, in which Valentine is falsely accused of trying to steal Winthorpe’s briefcase, the Duke brothers make a bet on whether nature or nurture is the determining factor in an individual’s life. The premise of the bet is that if they elevate Valentine from poverty, giving him all the things that Winthorpe has (money, a job, a network, and social status)—he will soon begin to act like a wealthy, entitled, successful elite. On the other hand, they wager, if they take away all that Winthorpe has, he will turn into a homeless, jobless, thieving degenerate.

The film is often seen as a combination of Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper and The Million Pound Bank Note, but it also touches on insider trading and the culture of poverty. Below, Atlantic editors Gillian White and Bourree Lam talk about the film and its relevance three decades later.

Gillian White: I hadn’t seen this movie in a really long time and I have to say, it hammers home the theme of economic inequality immediately. The opening montage is a long stretch of scenes that jump from the swanky home of Winthorpe to iconic Philadelphia landmarks to impoverished neighborhoods and homeless people. The point is, of course, to set the scene for the movie. But it also serves to prime the viewer to note that extreme wealth and excess and disturbing, abject poverty often exist within mere footsteps of each other in American cities.

Bourree Lam: Not only does that montage set up the landscape of inequality in urban cities, it also shows the economic contrast of black and white Americans that’s necessary for the plot. I’m not sure the racial or economic stereotypes in the movie would fly now, even as a plot device. But what I thought was interesting is the choice to demonstrate the stark contrast: Winthorpe wakes up Gossip Girl-style with a butler and breakfast in bed, a scene that comes directly after a glimpse of a homeless man sleeping on the street. Especially in post-Great Recession times, inequality in America is one of the most contentious issues in the country. I think the kind of contrast shown on screen in Trading Places would make us very uncomfortable now.

White: Agreed. To the cultural and racial aspect, there were many scenes with language or jokes that just wouldn’t be acceptable now. What felt enduring in some ways, albeit a bit extreme, were the professional aspects of the film. The Dukes are in the commodities business, which compared to the sectors portrayed in movies like The Big Short, The Wolf of Wall Street, and the original Wall Street, can seem kind of lame?

But I thought that the Dukes’ explanation of what the commodities markets were—betting on physical goods like gold, or wheat, or, in this case, orange juice—was fun to watch and easy to understand. I also thought Valentine’s response to the description of their role as commodities brokers—they explained they were tasked with executing the orders of clients who bet on whether goods would increase or decrease in price, and then collected fees for the service—was perfect: “Sounds to me like you guys are a couple of bookies.”

Lam: I loved that scene too! I liked that the things the Dukes chose to use in their explainer to Valentine are real items on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange: pork belly, gold, and “FCOJ”—frozen concentrated orange juice contracts. (They sound fake but they’re very real.)

I found their scheme—swapping Winthorpe and Valentine to see if people are a product of their environment and circumstance, rather than innate character and abilities—not only the most insane social experiment I’ve ever heard of, but largely rooted in the culture of poverty theory, the idea, popular among some academics at the time, that people who grow up in poverty adopt certain values and behavior that keeps them impoverished. (It fell out of intellectual fashion for victim-blaming and not matching empirical data, but apparently it’s made a comeback in recent years.)

Ultimately, the Dukes are proven “correct” in their assumption that American inequality can be explained by a culture of poverty: Winthorpe, who went to Exeter and Harvard, when placed in the “worst social circumstance”—which to the Dukes meant being framed for a crime (aside: what kind of boss plants PCP on his employee?!), being jailed briefly, losing all of one’s physical property, social capital, and livelihood—becomes an antisocial criminal. That was pretty offensive.

But the opposite is perhaps equally as bad: Valentine—whom the Dukes deem to be from a “culturally disadvantaged” background that led him to a life of crime—becomes an elite when he’s given all the trappings of an upper-class American. Valentine even has impostor syndrome for a moment, where he’s really not sure people will buy it. To add to the perception of respectability, the Dukes start calling Valentine William instead of Billy, and they make him wear Winthorpe’s Harvard sports coat—clear signifiers that he’s an elite.

White: The idea that money was the cure to all the issues inherent to a lifetime of poverty or that all people, divested of their money and status would become violent criminals was, yet again, gross. It was all made worse that the bet was essentially just for bragging rights, showing how little the Dukes value human life. But luckily it all felt pretty fantastical, and so did the solution when Winthorpe and Valentine find out that they are both being played by the Dukes.

Winthorpe and Valentine learn that the Dukes were going to get the inside scoop on the orange juice contracts—the Dukes already bribed the person tasked with keeping the Department of Agriculture report about how orange crops were doing to give them the report a full day before it was released publicly. This allowed them to engage in a bit of insider trading and make a mint. Valentine and Winthorpe’s insane solution is to get even, replacing the report with a false one and then heading the commodities exchange to engage in some insider trading of their own, front-running the Dukes.

Lam: John Landis, the director, says they used real commodities traders as extras in that scene, and that it took him a lot of studying to understand Winthorpe and Valentine’s con. Basically the Dukes are insider trading, and Winthorpe and Valentine front-run them by first agreeing to sell FCOJ in April at $142 (an artificially inflated price, the product of the Dukes’ trying to corner the market), but the other brokers buy their contracts because they think prices will be even higher in the future, so it’s a deal. Once those contracts are set, Winthorpe and Valentine wait for the price to bottom out after the crop report comes out saying that oranges are doing just fine. Once the price drops to $29, they buy FCOJ futures at that price to fulfill the $142 contracts—so they win big.

That final scene made me a little nostalgic, as the commodities-trading pits at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange closed this past July. The CME pits in both Chicago and New York are no more, as computers have automated commodities futures trading. So it’s even more of a shame that, as Landis explains in an oral history of Trading Places, they weren’t allowed to shoot at the Chicago CME pit for the movie. That’s why they end up at the NYMEX pit at the World Trade Center.

White: That’s interesting, I was wondering why they were trading commodities in New York instead of Chicago. But I agree, just seeing the trading pits in action is one of the most fascinating parts of the movie, remembering that there was a time not so long ago when all of these high-level trades were made by people essentially running around a room, yelling at each other and gesticulating wildly. I think this helps remind us how quickly and dramatically things can change in terms of technology and culture—some of the things said and done in that movie just wouldn’t fly now. Conversely, it’s shocking and sad that some of the commentary on the vast divide between the haves and the have-nots has only become more relevant in recent years.

Lam: Another thing that’s been interesting in recent years is the lasting cultural impact of the movie in the commodities world. In 2010, the movie was mentioned by Gary Gensler, the chief of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, in a testimony to Congress. He said: “We have recommended banning using misappropriated government information to trade in the commodity markets” and then goes on to describe Trading Places’s orange-trading scheme! It turns out that before Dodd-Frank, using misappropriated government information for commodities trading was not totally legit, but also not illegal. Section 746 of Dodd-Frank is lovingly referred to as the Eddie Murphy Rule by industry watchers, in honor of Trading Places.