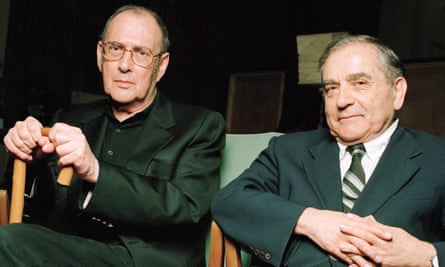

The actor Henry Woolf, who has died aged 91 after a series of heart operations, was also a poet, playwright and teacher, besides making a second career in Canada. But in Britain he is fated to be best remembered as the lifelong friend of the playwright Harold Pinter.

He was one of the “Hackney gang” of boys who bonded with Pinter at Hackney Downs grammar school in east London – a fiercely independent group who were as much at home discussing James Joyce and Buñuel as getting into street fights with Mosleyite thugs, and who cast a shadow over Pinter’s work from his early novel The Dwarfs to his last play, Celebration.

That was the first stage of the friendship (and I got to know Henry when Pinter introduced us). Stage two came when Henry, as a postgraduate student at the drama department of Bristol University, recommended a play by an unknown author and was asked to direct it. The author was Pinter, and the play did not exist; but within a week he had written it and in 1957 The Room made a modest stir in a converted squash court in a production by Henry, who also created the role of Mr Kidd the loquacious landlord.

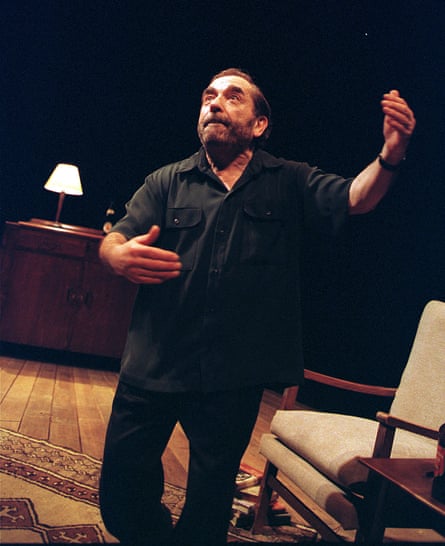

He returned to the role at the Almeida in 1999, by which time Pinter’s work was falling victim to what Henry called the “grim hand of reverence”, which could give his texts all the appeal of a building obliterated in scaffolding. Barely five feet in height, Henry had weight and authority on stage (aided by a raspingly resonant baritone), and it was a treat to hear the rhythms of the comic speech coming through as naturally as breathing.

He repeated this effect eight years later as Tubb in the National Theatre production of The Hothouse (a play dedicated to him). Tubb speaks for “the whole of the understaff” in the sinister Ministry of the play’s setting; and Henry made his entry with a long downstage march, wreathed in smiles and bearing a lighted birthday cake as if he owned the place. For anyone still in doubt, he clearly stamped the play as a sublime instance of a Carry On film gone wrong.

To limit any account of Henry’s life to his public performances would be a myopic misreading, as he was just as much an off-stage performer. With Pinter, he had developed a verbal shorthand dating back to the Hackney days, which formed one of their strongest links. There were other close points of contact – both nonbelieving Jews, both instinctively siding with the world’s underdogs, both poets.

Pinter became a man of wealth while Henry was often broke. But there were still moments of role reversal. Pinter paid for the publication of Henry’s first collection of poetry. In the 1960s Henry was co-habiting with a pet rat called Henrietta in a Kentish Town bedsit with paper-thin walls. Pinter summoned him to meet a friend and explained that he and Joan Bakewell were “in a bit of a fix ... we have nowhere to go.” Henry opened his doors to them, and then found himself in buses cruising round uncharted areas of Plumstead until the visitors retired to their grand houses and let him go home.

The friendship survived that test only to face another after Henry’s marriage to the much admired modern repertory actor Susan Williamson, whose career at the RSC had been cut short by Pinter. She saw him as a rank-pulling bully; which drove Henry into offering defensive concessions – “Be fair, Susan, he’s much nicer since he’s had cancer.”

Perhaps what finally kept their show on the road was an intimately shared language. When they said their last goodbyes, so Henry told me, it was in catchphrases from the wartime radio show Itma (It’s That Man Again).

Henry was born in Holborn, London – the youngest of six children in an immigrant Romanian family – to Caesar Woolf, a multilingual bookkeeper and his wife, Marie (nee Brill). As evoked in Henry’s 2017 memoir, Barcelona Is in Trouble, the household was one of much philosophising, little money and endless cups of tea. One early memory, foreshadowing the future, was of Henry’s first job at Paddington public library, which he recalls – rather than the theatre – as a “temple of magic”.

By his 30s, Henry had built an impressively eclectic acting record, from children’s television to working with stars and appearing in historic productions such as Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade (1964) and US (1966), and playing alongside Laurence Olivier in Ionesco’s Rhinoceros in 1960. But only once – as Toulouse-Lautrec in the musical-biopic Bordello at the Queen’s theatre, London, in 1974 – had he secured a lead on a major stage. He was known as a scene-stealing cameo artist, and seemingly forever confined to that platform.

Then, in 1978, he followed his scientist brother Louis to Canada, where he promptly won the Edmonton Critics award in 1979 for his solo performance in Heathcote Williams’s Hancock’s Last Half Hour (another piece dedicated to him), before finding a lasting home in Saskatoon at the University of Saskatchewan from 1983 until retirement in 1997 as head of drama.

In the academic world he did become a star. He could act, stage his own plays (notably Bim and Bub, a fable on the perils of belonging) and new work, such as the North American premiere of Pinter’s Ashes to Ashes. Most important, he discovered a love of teaching, and passing on his art and confidence to students.

He invited me to Saskatoon in 1998 and showed me over the campus, meeting ex-students whom he treated with a gentle authority I had not seen before. I also saw his production of The Merchant of Venice in which he played Shylock. A portrait of him in that role hangs outside the university’s Henry Woolf theatre. The production is the only one I have seen presented from Shylock’s viewpoint; I found it utterly convincing.

Henry was the funniest person I have ever met and an incomparable raconteur. Once begun, he would start building an endless crescendo which left his audience limp with laughter and begging for mercy. His comedy was perhaps linked to his interest in military history; an instrument of conquest. His poems could be funny too, but at their core was an Arctic of frozen despair; the sense of being cheated at birth into a game he was bound to lose.

This gradually changed into a posture of defiance, with the advice to “become a secret agent in your own life”, and cultivate an inviolable inner space so as to make the best of the game. From his life as a courageous artist, a joyously married man and the best of friends, it almost seems that he won.

He is survived by Susan, their four children, Sebastian, Marie, Hilda and Benjamin, and eight grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion