The Airship Club That Might Never Have Existed

In the 1960s, a house in Houston caught on fire. In the aftermath, a set of 12 scrapbooks were discovered. They depicted a society, the Sonora Aero Club, that had all but disappeared from history, if it was ever there at all.

The settlement of Sonora, about 130 miles east of San Francisco, was booming. It was there, in the saloon of one of the local boarding houses, that a group of men would get together every Friday night and talk of dreams. Well, just one dream, really: human flight.

They called themselves the Sonora Aero Club and, over time, they counted some 60 members, possibly many more. Their ranks included great characters, such as Peter Mennis, inventor of the Club's secret "Lifting Fluid," later described as "a rough Man, whit as kind a heart as to be found in verry few living beengs," despite being "adicted to strong drink" and "Flat brocke." The Aero Club's rules: Roughly once a quarter, each member had to stand before the gathered group and "thoroughly exercise their jaws" in telling how he would build an airship.

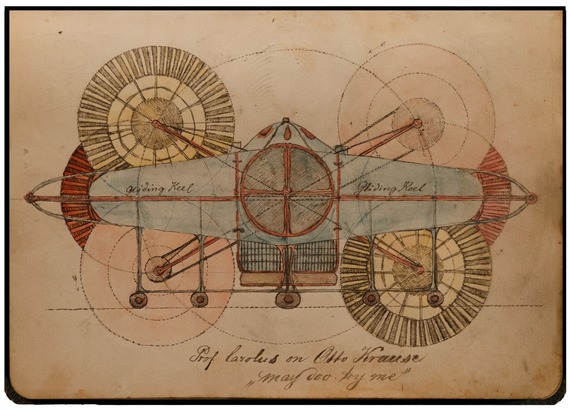

On one night in 1858, a man by the name of Gustav Freyer stood to present his invention: the Aero Guarda, an airship surrounded by a sort of hamster-wheel cage that would protect its passengers upon landfall. Freyer was a highly educated mechanic, and he waltzed up to the blackboard, took the chalk in hand, and began.

"Brothers," he said. "You all know I am not quite a professor." He looked at his fellow airship enthusiasts and continued: "I give you a nut to crack. My idea is to put a guard fence all around the machine to fall -- land -- easy and always safe, to keep some of you smarties from falling out." His contraption, he argued, would somersault upon hitting water, in such a way that the passengers would always "stay perpendicular, I mean head up on the floor of the hold."

He drew a sketch on the board and declared his work done.

"Well," he concluded, "now some of you have to pay the treat for me. Tell ya the truth, I am busted and dry as a fish!" And they bought him a beer, lifted up their glasses, and toasted his good health.

Or perhaps they didn't. Perhaps Gustav Freyer never stood up among his comrades and proposed this ridiculous design. Perhaps there was no Gustav Freyer, no Friday nights at the saloon talking about flight, no clink of the glasses to celebrate a new-fangled airship design.

Perhaps the Sonora Aero Club never existed at all.

One hundred years later, a house in Houston, Texas, caught on fire. In the aftermath, a fire inspector instructed the family to get rid of some of the old, miraculously unscathed junk in the attic. The family complied, and everything was soon landfill-bound.

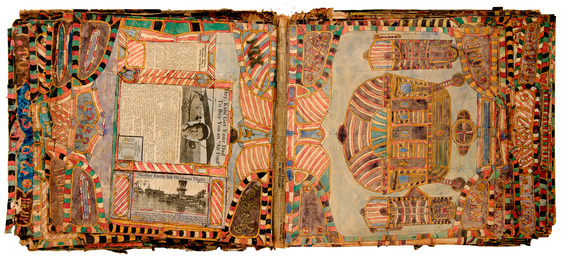

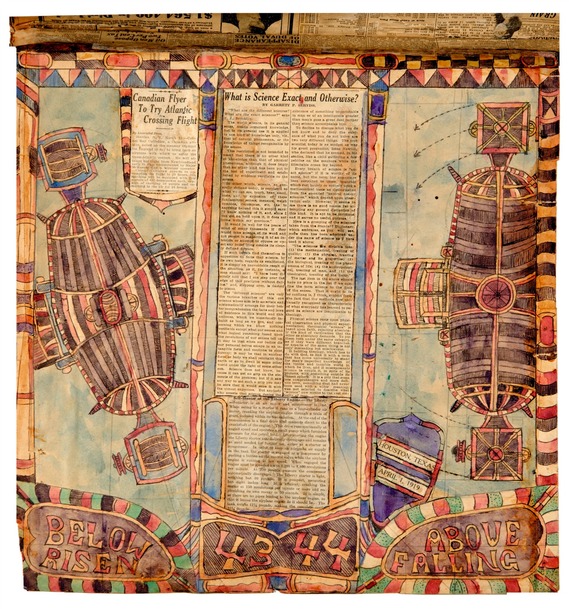

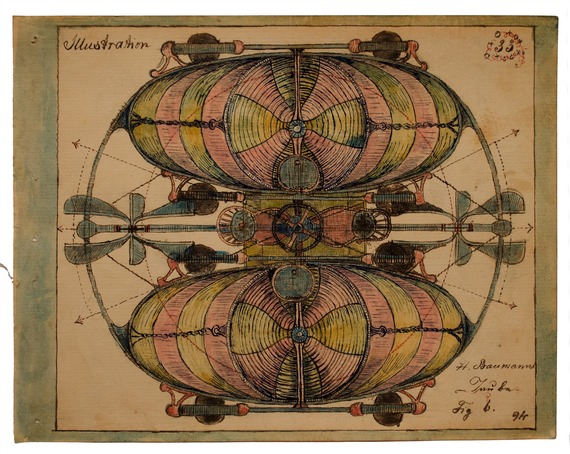

Among that debris: the 12 illustrated scrapbooks of one Charles August Albert Dellschau, German immigrant, supposed former Sonora Aero Club member. Created between 1908 and 1921, during Dellschau's retirement, the pages document his recollections of the machines, meetings, and men of the erstwhile Club.

"Dellschau's life-work was carried unceremoniously out into the light of day and literally left in a heap in the gutter," writes the late art critic Thomas McEvilley in a forthcoming volume about the artist.

But what could have been the artwork's death was its birth. As McEvilley puts it, "It was born into the gutter, you might say."

No one quite knows who rescued the books from their landfill fate, but soon they landed at Fred Washington's OK Trading Post. There they lay beneath some carpets, or maybe they were tarpaulins, until a student at a local university noticed them and brought them to the attention of a Houston art collector. By 1970, all 12 volumes had found more permanent homes. Dealers and historians eventually tracked down some additional Dellschau works, including a series of three journals called Recolections [sic], that also tell the story of the Sonora Aero Club and its inventions, with "ink drawings of fanciful airships that ... look for all the world as if they had flown off the pages of a Jules Verne novel," as flight historian Tom D. Crouch describes them.

All together, the shoestring-bound books contain some 2,000 pages, each a double-sided collage replete with calligraphy (often in a code that is still today only partially deciphered), drawings, and newspaper clippings. (Dellschau referred to the clippings as "press blooms," as though they were preserved flowers.) Each page -- or "plate," as Dellschau called them -- is dated and numbered, though the counting starts at number 1601. The estimated 10 volumes with the first 1,600 drawings are presumed lost or destroyed.

What are these scrapbooks? Are they an elaborate fantasy, spun out of the overactive imagination of an aging man? An outright delusion? Or are they earnest recollections of a lost time, a commemoration of the best years of a long, hard life?

Tracy Baker-White, a historian and former curator at the San Antonio Museum of Art, has spent 14 years trying to answer these questions. "This club -- whether or not it actually happened -- we don't exactly know," she told me.

"But," she continued, "I do believe he was in California and I do believe he had some experience that was important to him, that had to do with this, whether it was exactly as he depicted it or not in his later years."

Dellschau was born in 1830 in Berlin. Baker-White believes he most likely came to the United States in 1849, though any record of his arrival is uncertain. The first definite documentation of Dellschau in America that exists is from 1860, when he applied for citizenship from his home in Fort Bend County, Texas. That form makes reference to an earlier "declaration of intent" from 1850, indicating that that's when he arrived in America. Where was he, in that missing decade? Is it possible he was in the hills of California, searching for gold, debating designs of airships that could bring humans into the skies?

Baker-White thinks it is. Although there's no record of Dellschau in California, in his diaries, he makes references to people and places that are historically documented in California, such as a sheriff by the name of James Steward, who definitely did exist, and an innkeeper named Freund, who Baker-White says was also well-documented.

But as for the members of the club ... "This is the frustrating part," Baker-White told me. "I haven't found them in Sonora in the 1850s, but I've found them in Napa Valley in 1900, or in San Francisco in 1872, or in Stockton in 1872. There are possible links, but there's nothing that is in Sonora." There is, for example, she writes in the anthology, "a Peter Mennis who served in the Texas Mounted Volunteers during the Mexican War and died on November 1, 1901" who is buried in Napa.

So perhaps the members of the Sonora Aero Club later scattered to the four winds, but were very real -- and very much in Sonora -- at the time when Dellschau was there. Tens of thousands of men were streaming in and out of gold-rush towns during that time. Record-keeping wasn't exactly a priority.

But, at the end of the day, the club's historicity is thin at best. Peter Navarro, a graphic designer who purchased Dellschau's work after its landfill rescue (and later devoted decades of his life to studying and decodings the texts), wrote, "Many of the newsworthy events that Dellschau claimed to have happened while he was there have been verified. But those events dealing with the activities of the Aero Club have not." He concluded, "A personal search of records and cemeteries . . . have turned up nothing that would prove the members of the Aero Club ever existed." And though Baker-White can find some names in later California records, others crop up in turn-of-the-century Houston, where Dellschau lived out his later years and created his books.

All the signs seem to indicate that Dellschau's Sonora Aero Club is not exactly an accurate recounting of fact. But even as a fabrication, Dellschau's dreams represent a historical truth: This was a country seized with a dream of flight.

If Dellschau did go to California, which it seems that he did, it makes sense that he would have arrived there fantasizing about air travel: The journey westward was full of hardship -- whether over land across the American continent or by boat around Cape Horn -- many in America wanted to be in California without ever having to go through the trouble of getting there. Rufus Porter, the founder of Scientific American, published a pamphlet in 1849 entitled Aerial Navigation: The Practicability of Travelling Pleasantly and Safely from New York to California in Three Days.

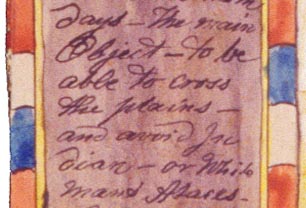

"Think about the fear that you would have going across this huge country, and encountering all kinds of hazards, and just being afraid," Baker-White remarked, "and how easy it would seem to just go across in a balloon." Dellschau himself expresses this desire, laden with the prejudices and racial tensions of the time, writing in the border of one plate that "the main Object [was] to be able to cross the plains -- and avoid Indian -- or White mans stares."

Drinking clubs, too, were common (one founded at that time -- E Clampus Vitus -- still exists). The whole idea that during the Gold Rush, a group of men would have gathered weekly to drink while concocting designs for balloons, dirigibles, and other flight craft is "totally plausible," according to Baker-White. It's more the specifics than the notion of the Sonora Aero Club that are historically suspect.

All of this was occurring during a time when people the world over -- not just westward-bound gold diggers -- could feel themselves on the cusp of an airborne age. Europeans of the 18th century were going absolutely nuts over air balloons, something Dellschau may have picked up during his formative years in Germany. But flight had obsessed humans for far longer. Crouch put it beautifully:

Flight was, after all, the great dream of the ages. It may have been the one technological dream that's innate in human beings -- because of the birds, because other creatures fly and we don't. It becomes -- the dream of flight becomes -- psychologically embedded in us, connected to those human desires to escape, to soar over obstacles -- whether geographic or obstacles in life.

That psychological landscape was in place and then, all of the sudden, in the late 18th century and into the 19th, with the advent of balloons, advances in mechanical engineering, and the harnessing of electricity, that long-held dream became a real possibility. "You have these waves of just raw enthusiasm sweeping through society," Crouch muses. He imagines a sort of collective realization, a moment when everyone took it all in, looked at one another, and exclaimed, "Gosh, you know, now we can actually do this!"

It is that air of possibility, that enthusiasm for human ability, that swells the pages of Dellschau's books. His fantasies weren't unhinged from reality, they were layered on top of it -- literally, in certain cases, as he painted the story of his Sonora Aero Club over the press blooms he pasted to the page, or in others less literally, as when he dreamt up what members of the club would have made of the new age of flight ("How would our members laugh, over the deeds of today's Aeronauts," he wrote on Plate 1856). This may be a feast of the imagination, but it had its inspiration in the veritable progress of the century.

* * *

Should Dellschau have wanted to improve on reality, no one could have blamed him. Following his time in California, he returned to Texas, where, as judged by all available evidence, his life was a hard one. He married a widow named Antonia Helt, which made him a stepfather to her daughter Elizabeth. He and Antonia soon had three children.

But in 1877 his life "began to unravel," Baker-White writes. He lost both his wife and son within a two-week period, possibly due to yellow fever which swept through the swamps of Texas around that time. He soon remarried, but his second wife passed away within a year. His daughter Mary "also disappears from historic records around this time and probably died."

In 1887 Dellschau moved in with his stepdaughter Elizabeth and her husband Anton Stelzig, the owner of a saddlery, at their home in Houston. He seems to have moved again, around 1890, to Austin in order to be near his one remaining blood relative, his daughter Bertha who was hospitalized there with tuberculosis. She died six years later -- the same year that Anton, at the age of 43, also passed away. Dellschau was, Baker-White writes, "63 years old and had lost two wives, three children, and a son-in-law. He moved in with his widowed stepdaughter, Elizabeth, and her eight children, including an infant and a toddler." It is in that house where, in 1898, Dellschau set to working on his memoirs and scrapbooks, and where, in 1923, he died, and where, in the 1960s, a chance fire would shove his art into the wider world.

And art it is. Whatever their historical value, Dellschau's works are treasures for their aesthetic sensibility. He's given us a visual expression of a time when the world realized that man might soon ascend beyond the terrestrial domain. "Renaissance paintings show saints and angels floating or flying around amid clouds in the same skies where Dellschau's angelic Aeros are suspended light as a feather," the art critic McEvilley writes.

Man was going up, and everyone felt it. As French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote, "Of all the metaphors, only those pertaining to height, ascent, depth, descent and fall are axiomatic. Nothing can explain them but they can explain everything."

We may never know whether the members of the Sonora Aero Club even tried to take to the skies over California. That is a question that, as McEvilley puts it, "is one of many questions that just have to be lived with as questions." But if they didn't fly in history, they certainly flew alongside it, a full-fledged society that once lived and thrived in the mind of Charles August Albert Dellschau.

Dellschau's work will be on view at Cavin Morris Gallery in May in an exhibition entitled "Restless II" and at the Pulse New York Art Fair May 9-12. A solo exhibition will appear at Intuit - The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago in September 2013. The monograph "Charles Dellschau," published by Marquand books and distributed by DAP Artbooks, will be available later this month.

Thanks to John Overholt for the original pointer and to Stephen Romano for providing the art that appears in this post.

%20Dellschau-2_cropped-thumb-570x460-116368.jpg)