The Case for the Politicization of Science

If you’re going to do something political, like a march, it should be political.

The sorrow of the March for Science did not hit me until I saw a photo from it—an older woman standing next to a homemade sign adorned with Ms. Frizzle.

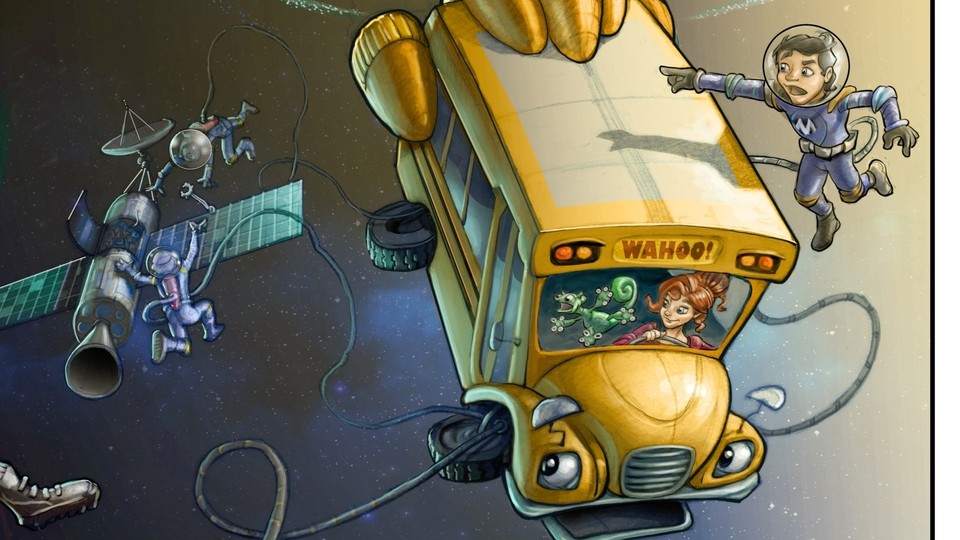

You know Ms. Frizzle, if only from a PBS ad. She is the elementary-school teacher with the curly red hair at the center of the Magic School Bus books and television show. In every episode, Ms. Frizzle corrals her small class of diverse kids into the Magic School Bus, which then drives to a local swamp, volcano, or human circulatory system. Then the eponymous magic happens—and the entire class is outfitted in hip waders, floating past a great blue heron; or in SCUBA suits, swimming through a vein past a red blood cell. Ms. Frizzle—not until recently did I notice her egalitarian title—lectures the class on the science of the scene.

No one ever signs a permission slip in Magic School Bus, raising questions about Ms. Frizzle’s management of liability risk. But no questions can be raised about her expertise, which seemed to hold the entire experimental curriculum together. She urged her students to “take chances, make mistakes, and get messy.” The world was bright and open and here for the curious.

Now, that remarkable and fictional woman—the discovery-obsessed doyenne whose face is in every public library in America—was here, on a sign, in the rain, near the White House, protesting a president who brags about grabbing women’s vaginas. I felt bad about the shabbiness of the whole scene, and I felt bad specifically for Ms. Frizzle, who, after a lifetime of teaching third graders, has to spend her twilight years doing… this.

It is a miserable time for science. America has an almost non-existent climate policy, its support for basic research is flagging, and its congressmen harass individual scientists in the name of ideology. At the March for Science last Saturday, the speakers and the protesters kept coming back to the same theme: “I can’t believe I have to march for science!”

But that was often as specific as they got. Before the event, organizers said that the march was not for any one particular political goal, but in support of science in general. This was not reflected equally across the event. The protesters who came to D.C. knew who their enemy was. (His name rhymes with Ronald Yump.) But the people on stage held a glorified science-museum presentation.

“This did not begin in November,” Rush Holt, the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a former congressman, told reporters last week. “It’s true the march idea came up in January, but it was built on a growing concern that reached a level of anxiety about the conditions under which science can thrive.”

This same tepidness also cooled the stage. Speakers encouraged attendees to vote, and they told them to call their representative in Congress. But they rarely funneled attendees to one group or another, or endorsed specific bills or policies. Far more often they reveled in their nerdiness or their shared love of science. Speakers were far more likely to praise historical Americans who took an enlightened view of science than they were to name contemporary ones who opposed it. One speaker singled out Abraham Lincoln for praise—not because he won the Civil War—but because he was so nerdy that he filed a patent.

Exxon Mobil files about 320 patents per year. It employs thousands of scientists. It devotes tens of thousands of dollars to scholarships which support women and minorities in STEM fields. An important idea in the study of geological time scales is called the “Exxon curve,” because it was discovered by Exxon scientists. Exxon also spent $8.8 million last year lobbying American lawmakers. This was actually low: In 2008, it spent $29 million to lobby for the defeat of a climate-change bill.

By any account, then, Exxon loves science. It doesn’t need convincing that science is useful and helpful—certainly, science helps Exxon’s bottom line every day. But when it comes time to shape U.S. policy, Exxon looks out for something that it loves even more than science: itself.

The problem of our political system isn’t an insufficient love of science. Sixty-seven percent of U.S. adults think scientists “should have a major role in policy decisions,” as do nearly half of self-identified conservative Republicans. When you set aside the issue of climate change, Americans of both parties do equally well on tests of basic scientific literacy.

The problem facing the implementation of any kind of sensible climate-change policy—for example—is that many powerful organizations believe they would be harmed by it. Therefore they use the levers of power available to them to oppose it. The U.S. provides $700 billion in subsidies to fossil-fuel companies every year.

These companies are entering politics to protect their material self-interests. These firms may have too much power, but they are not using the political system in a strange way: Protecting your material self-interest is a valid thing to do in politics!

It is true that the status of “science” has changed in American politics, thanks in part to 20 years of party polarization over climate change. But once a depoliticized issue becomes politicized, its supporters can’t win just by shouting that it’s actually uncontroversial. We saw this strategy fail in 2016, when the Trump campaign politicized free trade—and the Clinton campaign responded that free trade wasn’t political. It will fail again for science now, unless its supporters make new arguments for it and win the fight on the merits.

Which is why the March for Science scared me. The worst possible thing for the march is that people believed the rhetoric they were hearing on the stage. It will not help them understand why, after two decades of evidence, the United States has yet to formulate a sensible and science-informed climate policy.

After the March for Science ended, a colleague joked to me: “If they really wanted to be scientific about this, they would have the march again next week.”

The thing is: They are. On Saturday, the March for Climate, Jobs, and Justice will take over downtown Washington, D.C., and dozens of other cities around the country. Unlike the March for Science, it is forthrightly political. It understands itself as part of the broad and intersectional left. It has even divided the route of the march into sections for different aspects of the progressive coalition: one area for labor, another for racial justice groups, another for religious leaders.

This may make some scientists bristle: Should science alloy itself with other members of a political constituency? Their concerns are understandable but misguided. I suspect that in the longterm, it’s the confidently political—confidently partisan—climate marchers who will have the right approach. If you’re going to do something political, like a march, it should be fully political.

In September 2009, tens of thousands of protesters filled the National Mall as part of the the first major Tea Party rally. (Officially, it was called “the Taxpayer March on Washington.”) One year later, more than 200,000 people attended the “Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear,” the dual Jon Stewart-Stephen Colbert rally. One of these marches allied itself with a party and followed up with local organization. The other rejected extremist politics—but it neither supported a party nor asked protesters to organize at home.

Seven years later, it’s the smaller Tea Party rally that still reverberates in our politics. So if scientists want to do politics, they should do it all out. They shouldn’t worry about the stain of asserting their self-interest. They should take chances—they should get messy.