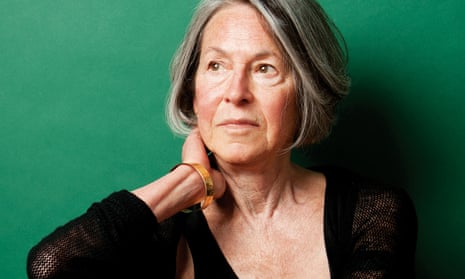

Readers who follow American poetry closely noticed Louise Glück in the 1970s. The rest of the literary world mostly took her Nobel prize last week as a surprise. And no wonder. She is not particularly topical, nor internationally influential; like the sadder-but-wiser adults who populate her later work, she can seem to keep her own counsel, to withdraw. That attitude is not so much a limit as a condition for her success, over a lifetime of serious, often terse, introspective, unsettling, sometimes exhilarating work. Like all authors of her calibre she harbours contradictions. Read her 12 collections (and two chapbooks) of poetry for the first time, and they may seem almost all of a piece. Read them again, though, and the divisions pop out: she has said that she tries to change, to challenge herself, even to reverse direction with each new book, and if you go deep enough you can see how she’s right.

Do not begin at the beginning; Firstborn (1969) was apprentice work. Instead, look at poems from The House on Marshland (1975) and the volumes that followed (available in the UK as The First Five Books of Poems). These elegantly laconic pieces portrayed women or girls seeking certainty and stability in a world whose only stable truths were grim. Glück’s version of Gretel, after escaping the witch, cannot stop imagining the oven in which her brother almost died: she feels as if she had not saved him. A poem called “Here Are My Black Clothes” begins: “I think now it is better to love no one / than to love you.” “Love Poem” condemns a lover or an ex: “No wonder you are the way you are, / afraid of blood, your women / like one brick wall after another.”

Early Glück wasn’t always that bleak, but she came close, in works that described many people, many difficult families, many adults’ rough choices, rather than stacking up details from her own life. The Triumph of Achilles (1985) expanded her repertoire of myths and scenes, of aphorisms and insights, without alleviating the sadness: a dream vision of stacked oranges in a marketplace, apparently a refuge for a lonely girl, concludes: “So it was settled: I could have a childhood there. / Which came to mean being always alone.”

Glück’s father helped invent the X-Acto utility knife, often used for crafting, a hard-to-resist metaphor for the cutting precisions of Glück’s poetry. After an eating disorder derailed her teens on Long Island, Glück spent her early 20s not in college but in extensive psychoanalysis: “I’ve learned to hear like a psychiatrist,” she wrote in Ararat (1990). That volume placed family stories at the forefront: the long, almost chatty scenes in poems such as “The Unreliable Narrator”, might resonate with readers who had difficult early lives. “A Fable” revised the legend of King Solomon: “Suppose / you saw your mother / torn between two daughters: / what could you do / to save her but be / willing to destroy / yourself?” If the poems were confessional, they were self-consciously, self-accusingly so, taking potentially life-wrecking traumas as matter of fact statements: “My son’s very graceful, he has perfect balance, / He’s not competitive, like my sister’s daughter” (“Cousins”).

These self-scrutinies remain some readers’ favourite poems. For others, though, they feel like run-ups to Glück’s thunderclap of a volume, The Wild Iris (1993), which won a Pulitzer prize. Most of its component lyric poems have nonhuman speakers: flowering plants, moss, trees and God. Through such masks, the poet addresses a creator on behalf of the whole creation: “You made me; you should remember me.” (Petals and leaves make good heavenly respondents because their life cycles are perfect fits for no single human being.) “Daisies” even wrong-foots poetic sceptics by asking whether the feelings Glück chronicles matter: “Go ahead. Say what you’re thinking. The garden / is not the real world … It is very touching, / all the same, to see you cautiously / approaching.”

Glück wrote in her first collection of prose, Proofs & Theories (1994), that she tried to make each of her books abjure a strength from the last: she never stopped making demands on herself. Having established her strength in mythic lyric, autobiography and pastoral allegory (talking flora), she moved to epic and to comedy. Her next volumes – from Meadowlands (1996) through Averno (2006) – cohere around the dissolution of a marriage, attempts to rebuild life in middle age, and around the epic journeys of travellers and heirs, from Dante to Homer’s Telemachus, sometimes treated for bathos. “I thought my life was over and my heart was broken. / Then I moved to Cambridge,” Vita Nova (1999) ends. She has made Cambridge, Massachusetts her home ever since.

By this time she was thoroughly famous, with a National Book Award, a job at Yale, and many other honours. Another poet might have concentrated on her public opportunities, to the detriment of her verse. Glück took those opportunities, judging the Yale Younger Poets contest and serving as US poet laureate consultant in 2003-04, but she also found new channels for her own work. A Village Life (2009) takes place in a pastoral setting not unlike northern Italy, where peasants and artisans keep up the loves and griefs of an unambitious era. “Young people move to the city, but then they move back. / To my mind, you’re better off if you stay, / That way dreams don’t damage you.” Her most recent book of new poems, Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014) – also her first to include many prose poems – follows the life of a made-up elderly writer, beginning in earliest youth, when “I could speak and I was happy. / Or: I could speak, thus I was happy.” But such happiness cannot stay: mature, “he lay on the cold floor of the study watching the wind stirring the pages, mixing the written and unwritten, the end among them” (“The Open Window”).

Glück’s poems face truths that most people, most poets, deny: the way old age comes for us if we’re lucky; the way we make promises we cannot keep; the way disappointment infiltrates even the most fortunate of adult timelines. She’s not a poet you read to cheer yourself up. She is, however, a poet of wisdom. And her declarations, her decisions, her conclusions, build and displace one another as the poems go on: even the sharpest claims require their poetic frames and contrasts. A Glück book can seem both visceral and cerebral, full of thought and full of grit and pith. If the earliest successes echoed Sylvia Plath, the latest reach beyond American poetry, to the melancholy generosity of Anton Chekhov, the shifting perspectives of Alice Munro. All poets come from somewhere; no poet speaks for us all. We can say, though, that Glück’s plain lines and wide views address experience common to many: feeling neglected, feeling too young or too old, and – sometimes – loving the life we find.

TELESCOPE

by Louise Glück

There is a moment after you move your eye away

when you forget where you are

because you’ve been living, it seems,

somewhere else, in the silence of the night sky.

You’ve stopped being here in the world.

You’re in a different place,

a place where human life has no meaning.

You’re not a creature in a body.

You exist as the stars exist,

participating in their stillness, their immensity.

Then you’re in the world again.

At night, on a cold hill,

taking the telescope apart.

You realize afterward

not that the image is false

but the relation is false.

You see again how far away

each thing is from every other thing.